Garrity Rights protect public employees from being compelled to incriminate themselves during investigatory interviews conducted by their employers.

This protection stems from the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which declares that the government cannot compel a person to be a witness against him/herself.

For a public employee, the employer is the government itself. When questioned by their employer, they are being questioned by the government. Therefore, the Fifth Amendment applies to that interrogation if it is related to potentially criminal conduct.

Garrity Rights stem not just from the Fifth Amendment, but also the Fourteenth Amendment. While the Fifth Amendment could be said to apply only to the federal government, the “equal protection” clause of the Fourteenth Amendment makes the Fifth Amendment applicable to state, county, and municipal governments as well (determined by the United States Supreme Court in 1964’s Malloy v. Hogan)

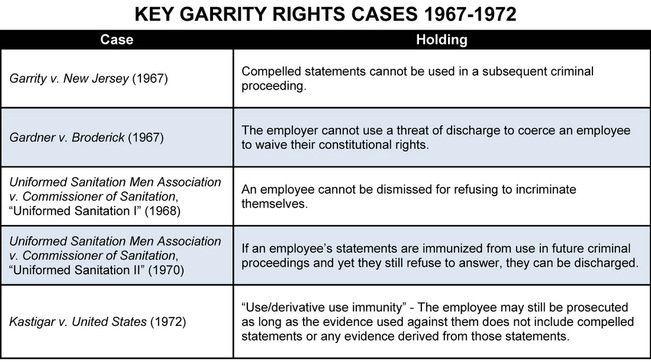

Garrity Rights originate from a 1967 United States Supreme Court decision, Garrity v. New Jersey.

The Garrity Story

The U.S. Supreme Court then ruled in 1967’s Garrity v. New Jersey that the employees’ statements, made under threat of termination, were compelled by the state in violation of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. The decision asserted that “the option to lose their means of livelihood or pay the penalty of self-incrimination is the antithesis of free choice to speak or to remain silent.” Therefore, because the employees’ statements were compelled, it was unconstitutional to use the statements in a prosecution. Their convictions were overturned.

Several subsequent cases further clarified the protections that fall under the umbrella of Garrity Rights:

Garrity Rights in the Public Workplace

Whether his Garrity Rights come into play depends primarily on whether he is compelled to answer questions. If he faces little or no penalty and then makes statements, his statements are voluntary. However, if he faces a sufficiently severe penalty for refusing to answer, courts would generally hold that his statements were compelled and thus their use in a future criminal proceeding would be unconstitutional.

The most commonly-threatened penalties that bring about compulsion are a threat of dismissal or a threat of disciplinary action “up to and including termination.” However, in some places, “up to and including termination” may NOT be considered compulsion; see the FAQ for more on this issue.

This scenario could unfold in a number of ways:

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SCENARIO 1.

Our city sanitation worker meets with his supervisor regarding the allegations that he has been selling illegal drugs. The supervisor advises him that his participation in the interview is completely voluntary and he can refuse to answer questions at any time, with no penalty for doing so. He is also advised that his answers may be used against him in a criminal proceeding. During the course of the interview, he admits that he sold drugs to his co-workers. For this violation of city policy, he is terminated. His admission is turned over to law enforcement and is used as evidence to prosecute him. Bottom line: he had no immunity because his statements were voluntary, not compelled; voluntary statements can be used in prosecutions.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SCENARIO 2.

Our city sanitation worker meets with his supervisor regarding the allegations that he has been selling illegal drugs. The supervisor advises him that his participation in the interview is completely voluntary and he can refuse to answer questions at any time, with no penalty for doing so. He is also advised that his answers may be used against him in a criminal proceeding. He is asked about the allegations and refuses to answer, asserting his rights under the Fifth Amendment. The supervisor cannot take adverse action against the worker for his assertion of his rights. Bottom line: lacking immunity, the employee can stand on the Fifth Amendment and decline to participate, without repercussion for doing so.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SCENARIO 3.

Our city sanitation worker meets with his supervisor regarding the allegations that he has been selling illegal drugs. The supervisor advises him that he is ordered to cooperate, and that if he refuses to answer questions, he will be dismissed from his job. During the course of the interview, the worker admits that he sold drugs to his co-workers. The employer can discipline or terminate him for the violation of city policy, but his statements cannot legally be used as evidence against him in a prosecution. Bottom line: compelled statements are protected from use in criminal proceedings.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

SCENARIO 4.

Our city sanitation worker meets with his supervisor regarding the allegations that he has been selling illegal drugs. The supervisor advises him that he is ordered to cooperate, and that if he refuses to answer questions, he will be dismissed from his job. Despite this, the worker still refuses to answer questions, asserting his Fifth Amendment privilege. The worker is lawfully terminated for insubordination. Bottom line: the employee’s statements were made immune by the supervisor’s act of compelling them; once the employee’s statements are protected, he can no longer refuse to answer.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Often, public employers will simply want to conduct an administrative investigation in order to ascertain whether misconduct has occurred, and to determine if disciplinary action is warranted. Accordingly, many public employers begin investigatory interviews by asking employees to sign “Garrity Statements,” “Garrity Advisements,” or “Garrity Warnings.” Once signed, a properly-worded statement enables management to question the employee and require that they respond.

The courts have not been consistent in their interpretation and application of Garrity Rights. As a result, certain aspects of Garrity Rights are interpreted differently, depending on where one lives. See the FAQ for more information.